You have to think about Germany for a second.

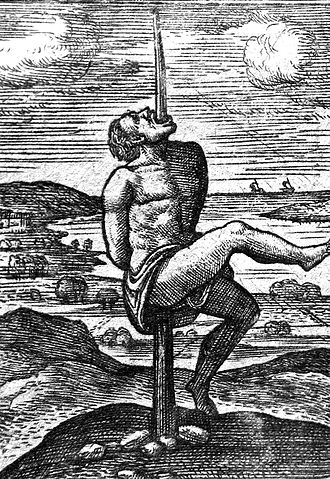

It's been 77 years since the end of World War II. In the first half of the 20th century, the "German problem" was the security issue of the day. Germany unified so late compared to the other major European powers, and emerged so strong in its historically accelerated state modernization, by the beginning of the century it had already begun to shift the world balance of power and was now demanding its "place in the sun."

At the end of World War II, American policy was unconditional surrender, for both Germany and Japan. The defeated Reich was divided into four zones of occupation. Nazism and militarism were to be obliterated forever. During the Cold War, the policy of the Western powers was to "to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down." This was the new world order.

The enormity of Germany's attempt at world domination, its abominable program of extermination of an entire race of people, the ignominy in its conviction for crimes against humanity, forced a complete reegineering of German society. In the decades after the war, the new Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) emerged as a model of the progressive humanitarian state in world politics. It joined NATO, formed the European Economic Community (now the E.U.), and developed one of the largest and advanced economies in the world.

"Never again" had been the call on the continent of Europe. Never again should Germany rise to hegemony and threaten the survival of an entire civilization.

And now here we are. Germany's going to actually rearm? Just the phrase "German rearmament" used to send shivers down the backs of leaders in the diplomatic halls of Europe. Now Germany's expected to increase defense spending by 2 percent. But how about in 2032? In 2042? How large will it be then? Shall a new German Reich be declared?

Most of those who lived through the "nightmare years" of German rearmament and war are no longer with us. Few voices are left to urge vigilance against the return of darkness and evil. Yet, we're in such a significant period, the message can't be dismissed or forgotten. There's a real shift afoot. It may not seem as dramatic as the end of the Cold War --- which shifted world power from bipolarity to unipolarity --- but the return to multipolarity will have epoch consequences.

Stay with me, folks. It's something I'll be paying a lot of attention to.

In any case, at the New York Times, "In Foreign Policy U-turn, Germany Ups Military Spending, Arms Ukraine":

Germany agrees to strengthen its military in the latest foreign policy about-face, amid pressure from allies and horror at Russia’s attack on Ukraine. BERLIN — It took an invasion of a sovereign country nearby, threats of nuclear attack, images of civilians facing off against Russian tanks and a spate of shaming from allies for Germany to shake its decades-long faith in a military-averse foreign policy that was born of the crimes of the Third Reich. But once Chancellor Olaf Scholz decided to act, the country’s about-face was swift. “Feb. 24, 2022, marks a historic turning point in the history of our continent,” Mr. Scholz said in an address to a special session of Parliament on Sunday, citing the date when President Vladimir V. Putin ordered Russian forces to launch an unprovoked attack on Ukraine. He announced that Germany would increase its military spending to more than 2 percent of the country’s economic output, beginning immediately with a one-off 100 billion euros, or $113 billion, to invest in the country’s woefully underequipped armed forces. He added that Germany would speed up construction of two terminals for receiving liquefied natural gas, or LNG, part of efforts to ease the country’s reliance on Russian energy. “At the heart of the matter is the question of whether power can break the law,” Mr. Scholz said. “Whether we allow Putin to turn back the hands of time to the days of the great powers of the 19th century. Or whether we find it within ourselves to set limits on a warmonger like Putin.” The events of the past week have shocked countries with typically pacifist miens, as well as those more closely aligned with Russia. Both have found the invasion impossible to watch quietly. Viktor Orban, the pro-Russia, anti-immigrant prime minister of Hungary, who denounced sanctions against Russia just weeks ago, reversed his position this weekend. And Japan, which was hesitant to impose sanctions on Russia in 2014, strongly condemned last week’s invasion. In Germany, the chancellor’s speech capped a week that saw the country abandon more than 30 years of trying to balance its Western alliances with strong economic ties to Russia. Starting with the decision on Tuesday to scrap an $11 billion natural gas pipeline, the German government’s steps since, driven by the horror of Mr. Putin’s attack on the citizens of a democratic, sovereign European country, mark a fundamental shift in not only the country’s foreign and defense policies, but its relationship with Russia. “He just repositioned Germany strategically,” Daniela Schwarzer, executive director for Europe and Eurasia at the Open Society Foundations, said about Mr. Scholz’s address. Germany, and especially the center-left Social Democratic Party of Mr. Scholz, has long favored an inclusive approach toward Russia, arguing about the danger of shutting Moscow out of Europe. But the images of Ukrainians fleeing the invasion dragged up older Germans’ memories of fleeing from the advancing Red Army during World War II, and triggered outrage among a younger generation weaned on the promise of a peaceful, unified Europe. On Sunday, several hundred thousand Germans marched through the heart of Berlin in a demonstration of support for Ukraine, waving signs that read “Stop Putin” and “No War.” Appealing to Germans’ commitment to European unity and the deep cultural and economic ties that reach back centuries, Mr. Scholz placed the blame for Russia’s aggression squarely on Mr. Putin, not the Russian people. But he left no doubt that Germany would no longer sit back and rely on other countries to provide its natural gas, or its military security. “The narrative that Scholz employed today is there to last,” Ms. Schwarzer said. “He spoke about responsibility to Europe, what it takes to provide for democracy, freedom and security. He left no doubt that this has to happen.” The country’s firm repudiation of its horrific Nazi past meant that it had long adopted a foreign policy of diplomacy and deterrence. But since the Russian invasion, many of Germany’s allies have accused it of not doing enough to fortify itself and Europe. Germany pledged in 2014 that it would increase its military spending to 2 percent of its overall economic output — the goal set for NATO member states — within a decade, but projections had shown the government was not on track to meet that target, even as that deadline approached. The topic had long been a source of conflict between Berlin and Washington, which spends more than 3 percent of its G.D.P. on defense. The debate escalated under former President Donald J. Trump, who would regularly berate the German government for failing to carry its weight in the alliance. In his speech, Mr. Scholz proposed that the military spending be anchored into the country’s constitution. That would ensure, he said, that the country would not again find itself with a military force of soldiers equipped with rifles that misfire, planes that can’t fly and ships that can’t sail. And he made clear that the doubling down on defense was for Germany’s own good...